- Home

- Products

- Sound Tech and PA

- Sound Tech DVDs & Downloads

- Free Tech Resources

- Free Sound Tech Lessons

- Playing By Ear

- Play By Ear DVDs & Downloads

- Ear Training & Music Theory Resources

- Worship Leading

- Worship Leading Course Downloads

- Free Worship Leader Training

- Free Worship Leader Resources

- Worship Band Skills

- Band Skills DVDs & Downloads

- DIY Worship Team Workshops

- Free Worship Team Training

- Free Worship Team Resources

What chord comes next in a song?

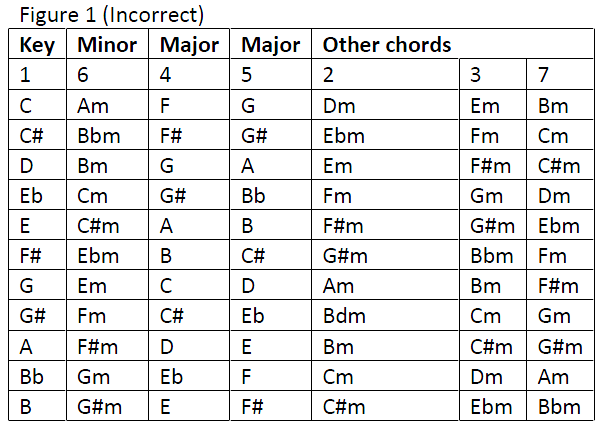

One of the members of the Musicademy website sent me what you can see in figure 1 below. He struggles with playing by ear and remembering the chords in common keys so he came up with this little chart that he sticks to his keyboard or guitar when he leads worship. The basic idea is that it’s a quick reminder of the 1st 4th and 5th major chords in each key plus the easiest to hear minor, chord 6, otherwise known as the relative minor. Then the three boxes to the right add the other chords that you might find if those don’t fit.

I suspect quite a lot of you have done similar things to help you play by ear at various times in your development as a musician. If you’ve done a bit of music theory you’ll spot some of the mistakes straight away but what struck me was how so many musicians make those exact same mistakes. Most people who have been playing a while have a partial understanding of the chords that come up in familiar keys but where it gets confusing for most people is in the same two areas that this chart runs into difficulties.

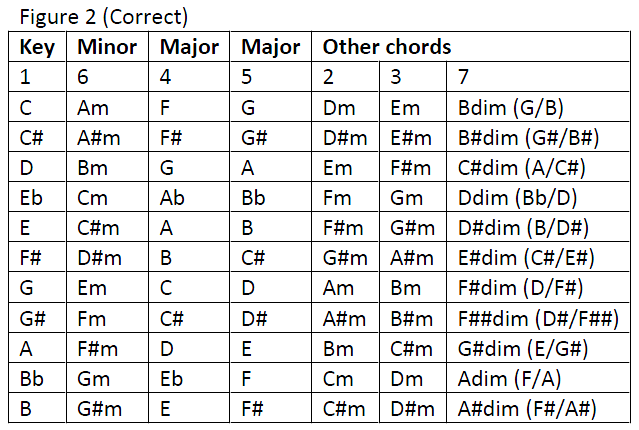

The first is naming chords correctly. Getting the right names for chords isn’t so much about being pedantic but more about learning a language that will radical transform your ability as a musician to transpose, communicate and even create arrangements and sounds for new songs. When our friend here plotted this chart he got most of the chord sounds right, just some of the names wrong.

This often happens because we (especially guitarists) often learn by a visual copy and play method. So when we learn a chord e.g. Ebm, the naming of it helps us commit it to memory and so in our head that becomes Ebm, forever. To think of it as D#m can add another layer of confusion and something else to commit to memory that doesn’t seem entirely necessary at the time. But this is all really easily corrected by applying three simple rules:

1. In every key you must have only one of each alphabetical letter between A and G

2. You must never miss out any letters

3. You never mix sharps and flats together in the same key.

So compare the key of B in both figures. Figure 2 avoids confusion because we now only have one version of E and it’s a major. Together with the consistent chord pattern across every major key, (1 major, 2 minor, 3 minor, 4 Major, 5 Major, 6 minor, 7 diminished) working out chords by ear becomes a much easier and more predictable task.

I know it’s sometimes easier to think of Eb in the key of E rather than D# because sharp keys are less spoken about, but if you can get in the habit of thinking about the chords with their correct names for their relative keys it will really help in the long run. In the keys our friend listed it does mean we need to have an E# and B# notes or in the case of the key of G# – an F##! These double sharps genuinely exist in theory, although in practice it’s why some people favor songs in flat keys rather than sharp ones. So it might be easier to think of G# as Ab.

The second difficulty is remembering what the less commonly used chords are, particularly the 7th chord in the key, displayed here in the box at the far right of the chart. So again looking at figure 2, the 7th chord is technically a diminished, which is like a minor but the 5th note is also flattened. If you play the diminished it sounds quite jazzy and dark. So in pop based music, (i.e. most modern worship music) if we want to use the 7th bass note we would more often play a 5 chord with the 7th bass note added to it. (5/7)

We do a lot of this chord understanding on all of our intermediate level DVDs as I think it’s such an important part of developing as a musician. But however you learn chords in keys, applying the three simple rules will help quicken your memory when you suddenly have to play that familiar chorus in G# and you’ve lost your capo or you can’t find the transpose button.

The course that focuses on learning to play by ear and teaches all the theory behind chords in a key is Play By Ear, Improvise and Understand Chords in Worship.

Free Band Skills course with all Musicademy or Worship Backing Band DVD orders

Free Band Skills course with all Musicademy or Worship Backing Band DVD orders  Free gift with all Musicademy and Worship Backing Band DVD orders

Free gift with all Musicademy and Worship Backing Band DVD orders  Worship Training Day Ealing London 5 November 2022

Worship Training Day Ealing London 5 November 2022  How to get maximum exposure for your song writing

How to get maximum exposure for your song writing  Streaming online church services: the tech, the tips and the stories from around the world

Streaming online church services: the tech, the tips and the stories from around the world  What do you most struggle with as a worship musician?

What do you most struggle with as a worship musician?  Worship Leader Training: Beginning and Ending Songs Well

Worship Leader Training: Beginning and Ending Songs Well  Learn how to play by ear

Learn how to play by ear  4 tips for making good use of your mic

4 tips for making good use of your mic